L.E. Daniels has edited over 140 novels—many of them award-winning—and has written many short stories, poems, and one tremendous novel I recommend you all seek out, Serpent’s Wake: A Tale for the Bitten. Her Bram Stoker Award-nominated short story “Silk” appeared in Hush, Don’t Wake the Monster, and she is an active member of the Horror Writers Association, serving on its Mental Health Initiative Committee.

Serpent’s Wake is kind of like a dream, but the kind you don’t want to wake up from. A story about trauma and recovery, it’s the kind of novel that appeals to horror fans and non-fans alike, a story that is magically realist, but barely. A true story in the guise of a fairytale.

I met L.E. at this year’s NecronomiCon, where she served on a panel about editing for small presses. In what is becoming a tradition, she also released a new horror anthology to coincide with NecronomiCon, co-edited with Christa Carmen, Monsters in the Mills.

In 2022, the same team released We Are Providence: Tales of Horror from the Ocean State, a finalist for an Australian Aurealis Award.

An American expat, L.E. grew up in New England before finding her way to Australia, where she has lived for over two decades, working with independent publishers and where she now runs the Brisbane Writers Workshop.

As of October 6th, L.E. has a brand-new story in publication, “Hangman’s Coming,” which you can find in Hippocampus Press’s Where the Silent Ones Watch. (The whole table of contents is a doozy.)

L.E. cares about history, especially her family’s history, which crops up repeatedly throughout her work. We talked about her background, why horror, and how she became a professional editor.

Please enjoy the following interview with L.E. Daniels.

Content warning for discussions of abuse.

The following interview has been edited for organization and clarity.

Noah Lloyd: I desperately need to start with a line that appears in the acknowledgments of Serpent’s Wake. You thank “Stephen King, for answering my letter via typed index card precisely thirty years ago when I was seventeen.”

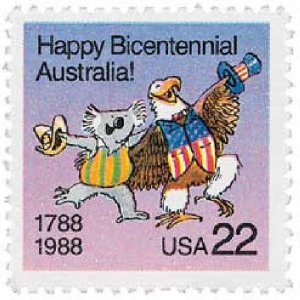

L.E. Daniels: I’ve still got it. It was March 1st, 1988. But the weird thing is—I’ll show you the index card. Actually, there’s a couple weird bits. The stamp shows an American eagle dancing with an Australian koala and saying, “Happy Bicentennial Australia.”

The other weird bit is that Serpent’s Wake was published March 8th, 2018, exactly 30 years later to the week. I wrote to Stephen King when the book was published, and I said, “Thank you. It took me 30 years, but I published my first book. And how did you know that this little Rhode Islander was going to end up in Australia?”

I remember seeing the stamp at the time. But it didn’t, you know, make an impression. I had no plans on living in Australia. There’s too many poisonous and venomous things!

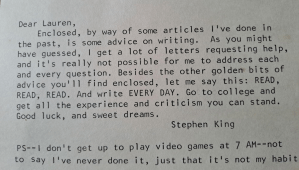

NL: [On seeing the index card.] Oh, it’s more than the single line you quoted in Serpent’s Wake. It’s a whole paragraph.

LED: He says:

Enclosed by way of some articles I've done in the past, is some advice on writing. As you might have guessed, I get a lot of letters requesting help, and it's really not possible for me to address each question beside the other golden bits of advice you'll find enclosed. Let me say this. READ, READ, READ, and WRITE every day. Go to college and get all the experience and criticism you can stand.

Good luck, and sweet dreams,

Stephen King.He didn’t sign it, but I don’t care. It’s right on my desk.

NL: In the acknowledgments, you said that you were 17 at the time. How did that hit you?

LED: I mean, it’s this great coming-of-age-for-a-writer story, too.

I’ve got to share this intimate detail: I’m 17 years old, I got IT for Christmas, which I requested from my parents. And my mom said, “I can’t believe I’m buying this for you. I’d prefer if you read Emily Dickinson.” I told her, “I have that, too.”

But I read IT. And when it was over, I felt like I’d lost my circle of friends. I was so involved with these kids. When it was done, I thought, “I want to be a writer, and I’m not going to joke about it anymore.” I was already writing poetry every night, and I thought, “This is what I want to do.”

I think my mom said, “Drop him a letter, see what happens.”

And so a few months later, I got that [index card]. At the time my grandmother was living with us, and she was kind of unstable and colorful. I’m happy to print that. We’ll talk about her later, because she inspires a few of my stories.

She was a fierce woman who came from New York City and worked in the mills. She and I were the only ones home when the letter arrived, because she was always in control of the mail. She’d go get the mail and bring it in the house and check what everybody got.

She hands this to me, and when I see “Bangor, Maine,” I burst into tears. We’re standing in the kitchen, and she starts yelling, “What’s wrong with you? You’re scaring me. What is this? What is this?”

And I clutched the letter to my chest and ran up the stairs, like, sobbing, and slammed my door, locked it, and read the letter.

So that’s how it unfolded. Isn’t that just dramatic and perfect for a 17 year old that’s going to be a writer?

NL: I love the detail of running up the stairs, clutching the letter to yourself. Very gothic.

LED: [My grandmother] was yelling the whole time. Whenever we were home alone, she’d get a little intense. I know she had undiagnosed mental issues that she was dealing with, because nobody had any diagnoses if they were born in 1910. And I just think that was part of the atmosphere.

She’s no longer with us, but she shaped me just like these characters shape us, and I’m grateful to her, and for such a rival in the letter story.

I do write about people, ancestors who I’ve met and who I haven’t met. And I ask them to be a part of the process.

NL: Since you said she was an influence on some of your writing, maybe we can keep talking about your grandmother for a bit. I’m imagining that [excellent, Stoker-nominated short story] “Silk” is maybe one of those places where she shows up.

LED: Yes. There are two stories actually, “Silk,” which is in Hush, Don’t Wake the Monster, and also “Darkness Repeats,” in Monsters in the Mills. I grew up listening to her talk about the mills, and honestly a good 90 percent of “Silk” is true.

However we want to describe it, it is handed-down, legacy material about my great-grandmother and her lack of control of her body. There was no birth control, so women relied on whatever they could privately, secretly, and worked.

There were no bathroom breaks [in the mills]. The mills were arduous. The silk mill was intense for these people, and my grandmother told me these stories of her whole life.

When she was a little girl, they used children to remove the silkworms from the cocoons, because they had small fingers, and a silk cocoon is one long filament. So a child’s fingers can peel the filament away and not break it.

So Nana would get a bucket of boiled cocoons, and that was her job. She would unfurl the silk. She was a child laborer, she didn’t do well in school—I do think ADHD was part of her situation—and she struggled.

But she thrived in the factory. She was the fastest. And she was determined, and she wanted to make money, so she worked in the wool mill as well, which is in “Darkness Repeats,” assembling the wool coats for the winter overcoats for the soldiers.

And she did bring $19 home a week when other women were making five to ten. She was proud of that.

NL: I’d love to talk about “Silk” a little more specifically. I was just kind of floored at how quickly we care about the protagonist. I was wondering if that was something you were aiming for intentionally, or thinking about at all?

LED: Yes, I really appreciate that question. And I really—I’m so grateful to hear that, because I took a risk writing in the second person.

You don’t read a lot of stories in second person. I tried to write [“Silk”] in third person limited, but it just wouldn’t work. I think because maybe it was the first story I’d written that had so much of my grandmother in it, I had to use a forceful case, you know, to capture who she was. And it just kept sliding into, “You do this, you do that.”

She was first-generation Italian, born in the U.S., born in the New York tenements in Harlem. And she was a survivor. She wasn’t wanted. She was the last child in a series, and they didn’t even name her. It took her a few weeks to get a name on her birth certificate.

She got all the hand-me-downs. And I wanted her to have that energy of a scrapper, a fighter. She used to sneak into the plays in New York City and eavesdrop and memorize the scripts and then come home and perform them. I wanted to capture her.

I do write about people, ancestors who I’ve met and who I haven’t met. And I ask them to be a part of the process. I approach them with, “Come on in, tell me what you want told. Tell me what you do here. Let’s make a good story with your truth in it.”

She spent her last couple of years in a nursing home because my mother just couldn’t handle her anymore. She was really difficult. And I imagine there was a lot of suffering, and a lot of regret. I tried to unpack that a little to help myself understand her, too.

I really like this idea, too, of show don’t tell character: the iceberg where you know this person, but you only let one-eighth of them appear in the story.

John Carpenter’s The Thing is one of my favorite movies, because it’s all show don’t tell. It’s just, here’s what you need to know about these people to make this story crackle.

There’s a book by Lisa Cron called Wired for Story; she talks about the neuroscience of storytelling and how we have a desire for story wired into our DNA. We want to try to understand, to slide into the point of view of the characters and unpack them.

We don’t want to be told that they’re angry or resentful. We want to see that play out. So I aim for that precision, that economy, and that emotional—just—unraveling. And hopefully it works.

NL: You said “unraveling,” and of course I started thinking about cocoons again. You mentioned that you tried to write “Silk” in third person and it just wouldn’t work. When you’re writing, how do you know that something’s not working? What instinct tells you that a piece you’re working on isn’t yet successful?

LED: There’s so much to this process that’s mysterious and difficult. And I think we do our best as editors and writers to get our hands around it. And we do our best to prove that it’s objective and not subjective at times, that there are rules and there’s consistency. And we’re trying so hard to manage all of these forces.

We don’t want to be told that they’re angry or resentful. We want to see that play out.

When a point of view doesn’t work, the image that pops into my mind is like pushing a river with a broom. I keep trying to change it to a third person point of view, and I keep sliding back to “you.” I keep writing sentences in second person. I’m not able to switch gears mentally.

That’s what happened with “Silk.” I started in second person, and said, “Oh God, it’s going to get rejected.” I was writing for Azzurra Nox‘s submission call for women in horror. I wanted it so badly. I mean, a Stephen King homage anthology, come on, I want to be in this.

I thought she’d reject the second person. It’s such a risk. But I would change it all to third and then I’d be writing new sentences in second. It was almost like Nana was just, “Now do it right.”

I hope that makes sense.

NL: It totally does.

We’ve brought up mills a couple of times, and Monsters in the Mills, a new anthology you edited with Christa Carmen, has just come out. What is it about mills that attracts you to them? In addition to the family relation, what makes them a fruitful site for stories for you?

LED: Oh, gosh. I want to see more stories about them.

I grew up in New England where mills pepper the horizon. You can go for a drive, and if you go for more than 15 minutes, you’re going to see a mill in the landscape.

I grew up on Aquidneck Island, where there’s Newport and all those mansions. A lot of the money came from the industrial age. Whale oil started it. They made the shoes for the Civil War soldiers. Those mansions in Newport are steeped in labor.

So I had that extreme, and then I had the stories coming from my family. But what I’d love to see is more writers exploring family history, because that’s what happens with Monsters in the Mills.

At the Monsters in the Mills launch party, many of the writers were saying, “I’d always heard the stories about my aunt, or my grandmother, or my father, but writing this story really connected me to their legacy and their memory and their stories. And I could do something with it and bring it back into the consciousness of the family—and also of readers.”

Mills are also treacherous places. I remember reading—quite young—Herman Melville’s “The Tartarus of Maids,” where he talks about the paper mills of Lowell. He sees the conditions of the workers and he’s horrified.

I didn’t know Melville did much more than, at that age, Moby Dick, and to know that he had that social consciousness was powerful for me—I think the mills are a place where writers are attracted to writing about social messaging, and understanding how we’re here today.

I think the mill is a symbol of so much, and when writers start to dig it delivers.

This is an area where great wealth came for the few. There’s a lot of the American story in here, and how our labor market and our labor conditions change, you know? I was reading recently about video games and how video game programmers can be overworked, and their conditions can be pretty stressful. There’s been some exposés on that in the last few years.

I think maybe this is a new kind of mill.

So it gets us thinking about how things don’t really change. Where we come from does help determine where we’re going, and if we’re savvy, we can just be a little more switched on.

I think the mill is a symbol of so much, and when writers start to dig it delivers.

NL: Still sticking with mills, what was the impetus for the anthology?

LED: Well, the introduction was written by Faye Ringel, and after doing We Are Providence, she said, “What do you think about doing a mills theme?” And she already had the title, Monsters in the Mills. We all just lit up.

Ricardo Rebelo is one of our authors and he knows so much about mills. He came on board for this, in our little group, and said, “Oh gosh, I know about how tuberculosis was passed through women blowing on the spindle, they shared illnesses. And then there was the arsenic and lead, all sorts of things.”

It was really credit to Faye Ringel with the idea. She’s an academic, and she’s brilliant and she’s just full of wonderful ideas.

NL: We talked about King already. I mentioned in an email to you that Serpent’s Wake seems to have a lot of Tanith Lee in it—

LED: Oh, gosh darn it. Thank you.

NL: —and “Darkness Repeats,” in Monsters, really struck me as like a working class gothic. I’d love to hear what some of your influences are, if you had to pick three or four.

LED: You know, I thought hard on this question because I want to come up with something different and new. First of all, I have credited my parents, because—with all this book banning going on—we were allowed to read anything in my house, anything, so long as we talked about it.

I was seven years old when the animated Watership Down came out. And I said, “Please take me. I don’t care about the General and the blood coming out of his mouth, please, I want to go. That’s my vibe.”

And my mom said, “You’re seven, you’re too young. Here’s the novel.”

I was so mad. But I read it—it took me like a year. I was really young and I went really slowly. I saw [the movie] maybe when I was ten. They finally caved in or something. And I remember understanding why my mom didn’t want me to see it.

Some other random bits that I only thought about because you asked this question:

When I was in fifth grade, I got my hands on a copy of Raymond Moody’s Life After Life in the school library, and I read all these accounts of near-death experiences. This is probably 1981.

I remember coming home with it. I must have been, what, ten years old, and showing my parents. They were saying, “Yes, good for you.” Also, in the same school library, there were horror story anthologies that were fantastic. I can’t remember the authors or anything, but there’d be a badly drawn wolfman on the cover. I would just take these things home and chew through them.

My oldest brother handed me old issues of Asimov. Oh, there was this collection called, The Fourth Galaxy Reader. It’s all short story science fiction. I just ate this stuff up.

Then getting a little older, I remember reading “The Night Face Up” by Julio Cortázar in ninth grade, and I felt like we finally got a story that was awesome.

Julio Cortázar—he was handsome, too. There was this little black-and–white photo of him. He was handsome and he loved motorcycles. And there I was, probably 14, thinking, “Wow, he’s not this crusty old guy at a desk.” He was cool.

“Occurrence at Owl Creek” as well, by Ambrose Bierce. I read that around the same time. I thought, if this is what writers can do, I’m on board.

NL: I do want to want to press on a little, but first—the wolfman covers.

Why horror? This is maybe an impossible question to answer—which I often ask—but what do you think it was that, at such an early age, attracted you to this genre?

LED: Oh gosh, I love this question.

This is so important for horror writers to talk about. I was a child who had this typical, white, middle class kind of existence. But behind the curtains there was abuse going on. There was physical, there was sexual abuse.

It was not a direct member of my family, but it was in the ring of my existence. And it went on for years, creating complex PTSD, which, I mean, I’ve done the therapy. I’ve done all the work, I got the action figures, I got the t-shirt.

For me, horror was a way to put words and action and imagery around the secret things that were happening to me.

Actually, my t- shirt says “I’m fine” and it’s blood stained. [Laughter.]

For me, with all this going on, I was in love with TV 56 out of Boston’s Creature Double Feature. Every Saturday there were two horror movies that would play back to back. Sometimes there’d be Godzilla, sometimes it was Day of the Animals, or Attack of the Killer Bees or Piranha or The Blob. Sometimes it went all the way back to the fifties and sixties, and sometimes it was from the eighties.

And I ate it up. For me, horror was a way to put words and action and imagery around the secret things that were happening to me.

I also had a profound stutter, so I really was bullied in school. There was a chant for me on the bus, because I couldn’t say certain words. I look back now, and all of these factors attracted me to a genre where there was power, there was some form of justice.

I loved the movie Alligator, where people were flushing alligators down the toilet and one of them was eating dogs that were given growth hormones in a lab, their bodies discarded. So this alligator was growing to enormous sizes. And to see this alligator bust into this rich party and just eat everybody, and throw people in the air—I think for me as a kid, that was just like, “Yeah! The tables have turned.”

There’s justice, even if it’s chaotic. I think now that’s in the background, working away on me.

I am a member of the Horror Writers Association’s Mental Health Initiative Committee, and I love the things that we talk about there, and how people write about grief and write about trauma, and write about loss, and write about addiction, and what it’s like to be an outsider, whatever that means for people.

They create something that’s a catalyst for social change, in my mind. So now I’m doing that with my ancestry, and trying to find what happened in my family and unpack it for social relevance today. I think that’s where I can get away with so much in horror.

Like Oscar Wilde said, “Make them laugh or they’ll kill you.”

In horror, it’s scare them or they’ll kill you.

That’s really a nutshell of my experience. Today, I’ll be napping to Hannibal and my husband will come in and say, “How are you asleep to this?” I said, “Oh, it’s just so soothing. It suits my nervous system.”

That must be wild for some, but it makes sense for others.

In horror, it’s scare them or they’ll kill you.

NL: I just have to ask, are you listening to an audiobook of Hannibal the novel, or do you mean Hannibal the incredible TV show?

LED: The incredible TV show.

I do love Thomas Harris’s work. I’ve read all the books. I found Red Dragon when I was in my early twenties. It was just cerebral and gorgeous, and the characters were incredible. But the series—and I credit Geneve Flynn, one of my friends, she’s won Stokers and she’s just this talented writer—she bugged me and said, “You got to watch Hannibal.”

I was an Anthony Hopkins fan, and said, “No, I can’t. I can’t see it.”

But then this whole universe opened up. I mean, the set designs, the costuming, the dialogue. Oof, it’s just beautiful.

NL: I remember when a good friend of mine turned me on to Hannibal. And shortly after I started watching it, I texted her something like, “You know, this is making me want to start cooking again.”

LED: Right? Janice Poon is the the show’s chef. They told her, you have no budget, just do what you can. And that’s why the cookbook is so amazing. There’s punch romaine, which was served on the Titanic, and all these elaborate recipes—you can make little roses out of tomatoes. I mean, it’s just so beautiful. They hired all these experts to make this show something really special.

NL: Let’s turn to your novel Serpent’s Wake for a minute. I’m going to use a term that I hate, but I think that a lot of people would call it “magical realism.” There’s this one speculative spark at the very beginning, which we then return to at the end, but throughout, I kept expecting more overt horror elements. I loved that there never was, and that it was just an exploration of this character’s reaction to being swallowed by a snake for 12 years.

How did you make such a brave choice, one, in order to subvert those genre expectations? And then, two, how did you navigate just thinking about the novel as as a whole?

LED: Thank you so much for reading it and for this question. The shadow behind Serpent’s Wake was that I was a psychology major first. I was steered away from writing by my family with “You’ve got to have a real job.” So I did two years as a psych major, and had a class called The Psychology of Religion.

I wrote a screenplay about werewolves, and I got a C. If I cleaned it up and wrote about “women’s stuff,” I got an A. It was wild.

And for a moment the professor steered into Marie-Louise von Franz and Bruno Bettelheim and fairy tales, how they speak to the unconscious of children about rejection and abandonment, etc. I remember sitting there thinking—I was probably 19 years old—maybe I could write a story that spoke to the inner unconscious child, the inner child of an adult who’s been through trauma.

So the seed was planted many years prior.

Around the same time I changed to a writing major, and I said, “Well, the psychology won’t be lost.”

But then every time I tried to write horror, I was penalized. Imagine the late eighties, early nineties. I wrote a screenplay about werewolves, and I got a C. If I cleaned it up and wrote about “women’s stuff,” I got an A. It was wild.

This was at Fairfield University, where I went, which is all different now. They have classes on genre fiction now.

Then at Emerson, the same thing—I was steered away. And so I found if I wrote magical realism, I could get away with something, you know? I could have some of where I really wanted to be.

Serpent’s Wake was also about me getting away with something. I wanted to tell an allegory about post-traumatic stress and how people navigate this, especially after working with veterans. I worked in nursing homes and homeless shelters. I wanted to integrate the fact that a lot of this stuff’s the same, even if the reason people have trauma is different.

So this was using allegory, using nameless characters and nameless geography, which can still be traced, but as an inward map.

I hope that answers the question. But yeah, I think magical realism at its root is about getting away with something. It’s infiltrating colonized areas, where there is a strong First Nations voice, and where people are affected by the landscape and the spirituality of place.

They want to tell a story that’s different so there’s always decolonizing energy. So I think I did it because I felt like I had to tell the story a certain way, and I couldn’t just tell it straight. It’d be boring.

I think magical realism at its root is about getting away with something.

And at my heart there is a horror writer, and there is a weird fiction writer, too. So I think I was trying to get away with it. Now things are different. Young people taking university these days can do almost anything they want, and they can find somebody who will get it, you know?

NL: There’s so much I could ask about Serpent’s Wake, but before we run out of time, I do want to ask about your editing career. When did you first get interested in editing professionally?

LED: It was all accidental. I went to Emerson College while I was working full time for Ziff-Davis Publishing, and I had a really good boss. I’d been working there for about six years when I said to him, “I think I want to do a master’s degree,” and he said, “You know I’ll help you.”

I started with one class at a time. I was not enrolled in the program, I was doing it casually. I had a really good teacher, Sam Cornish, who’s taken the journey—he’s no longer here with us—but he kept encouraging me and saying, “You have smart things to say.”

I was terrified to speak in class, thinking, “I don’t read enough. I don’t write enough. I don’t know enough. All these people are so much smarter than I am.” And Sam encouraged me.

It would be 12 people in a class, and you’d be reviewing somebody’s manuscript and I would be too shy. Even if it wasn’t my night, I’d be so scared of saying the wrong thing. There was a lot of internal pressure.

But, eventually, I found that I could find things in people’s manuscripts. So it was really accidental, with great trepidation. And then the next thing I know, my boss’s wine guy is faxing me his manuscript, his thriller. I gave it a little mark-up and faxed it back and I think it just happened that way.

Then I ended up moving to Australia, and I found a little independent press, which was incredible—he’d be mad at me for saying that—an independent publisher, he’s got 400-and-something titles. I ended up working with him for 15 years, and then as a contract editor when he needed me.

I was thinking if I had one story to [explain] what editing does.

…the next thing I know, my boss’s wine guy is faxing me his manuscript, his thriller.

You’ve got this partnership between author and editor and, when it’s really working—I felt it with Monsters in the Mills and We Are Providence—I felt it on plenty of other projects, but this one story was about ten years ago.

I was working for the publisher here in Queensland, and we had a man from New South Wales who had spent a lot of time in the “-stan” countries. He’d written a novel, and it had been accepted, about why refugees keep coming to Australia, and fleeing these [other] countries.

He was looking to inspire Australians with some sympathy for people who keep showing up undocumented. It’s this excellent book about this young man who experiences a lot in Afghanistan.

[The book is Kafiristan, by Ross Howard. Content warning through the end of this response for sexual violence.]

It starts off in the country, it’s a small family affair. There’s a father who’s a teacher, a mother, a teenage girl, and a slightly younger teenage boy living in this mountainous village, when the Taliban moves in and changes the whole atmosphere. It becomes very frightening for everyone very quickly. The father speaks out, and he’s murdered, and the sister sexually assaulted violently.

So the mother decides to take her children away from there.

Under cover of darkness, they go. They put the sister, who’s very wounded, on the donkey, and they go off into the mountains towards the mother’s very remote village. And the son becomes the man of the house.

They make camp and the sister dies overnight.

How the scene was originally written, while the mother’s grieving, the son goes out and gets the donkey ready and then puts the mother on the donkey, and they have the sister’s body, and they proceed on to the mother’s village and I felt something was missing.

Emerson College taught me, [as an editor,] “Don’t write the story.” You don’t interfere with a writer’s creative process. I see that happen with a lot of writers groups, and I’ve been in writers groups where they’re like, “Well, if you just put a lady with a hat there…”

But sometimes you can word things respectfully, and you can help a writer achieve their goal, their vision, because you’ve become synched. So I phoned the author and said, “What if, when the mother’s grieving the daughter at the campsite, and the young man goes out to the donkey, he notices that the donkey is stained with his sister’s blood? Because let’s think about what you’ve set up. And what if he prepares the donkey so that the mother doesn’t have to see that?”

I kept it really short, and he said, “Oh my God.”

Within hours he came back with, I’m talking about maybe another couple sentences. And he sent this paragraph back to me, and we both had goosebumps. We were both a little teary. That’s about really getting to the emotional truth.

I think that encapsulates the magic of understanding an author’s goal and saying, “There’s this little missing beat. What happens if you just give it one more touch?”

NL: I think a lot of people think that editing is just line editing or copy editing, as opposed to the real contributions that a developmental editor can make.

LED: A lot of people come to me thinking they need a proofread, but their work needs more than that. I actually don’t like to proofread, and used do lots of it in the beginning of my career. And when I was working with this author, I was really just copy editing, but there were two structural edits that happened under that cycle, and one of them was the donkey, and the other was a very typical situation where he knew so much about an area and a condition, that he used dialogue between father and son right at the start to “info dump.”

“Hey Dad, what’s the deal with the Taliban?”

And Dad’s like, “Well, son, I’m a teacher. So I’m going to tell you.”

I highlighted that and said, “Let’s pepper it in.” It’s very tempting for writers to say, “Here’s a chunk of information.”

Things like that happen during the editing stage where we all need a little tap on the shoulder to say, make that a little more dramatically driven.

…we all need a little tap on the shoulder to say, make that a little more dramatically driven.

NL: When you embark on a new editing project, what are you thinking about when you’re accepting submissions, or you’ve gathered your submissions and are starting to winnow them down?

LED: It depends what I’m doing it for. I was one of the judges for the Poetry Showcase XI for the HWA. There were 220-something poems that we—there was a team of four of us—went through.

For an example like that, I think about what the poetry showcases are after, you know, using horror to communicate a scene or message, and having some kind of twist, within a little dramatic arc. Something suggestive of an experience for the reader and some sense of dread.

So I try to align with what I know the publisher wants or the organization wants. I recently judged a competition which was 1000-word short stories, and I know that publisher and I know what she’s after. So I align with her vision: a little bit of Australia, a complete story arc, a character arc, a change, a surprise.

But personally, if it’s a project like Monsters in the Mills or We Are Providence, and when I was working for Dr. David Reiter at Interactive Publications here in Queensland, it’s the social messaging that I look for most. I want people to explore the less represented, the secret stories who make us who we are, the challenges that we personally face with a personal emotional investment from the writer.

I know that investment works for me, when I write—for example, this sci fi story I just had accepted by 34 Orchard’s 2025 Darkness Most Fowl anthology was my very first science fiction [I’ve written] since I was a kid.

While I was writing, I got caught up in how plants are grown on the International Space Station as one of the themes. I watched all these videos, and when I began writing, I was very cerebral and dry. The energy amped up only when I dropped into the space of how I personally feel about mass extinctions and our negative impacts on our planet.

I had to force myself to feel how frightened I am when I consider the reality—we had a record-breaking heatwave here this August, for example, which is like having a heat wave in, say, late February for a New Englander.

A 90-degree heatwave. It was absurd. I have children, and I just think, what’s what’s going to happen for all of us, for them? So I had to go into those terrible feelings.

So when I feel that intensity in my work, or I feel that echo in someone’s submission, I know they’ve gone into that authentic space and are determined to tell the truth.

Or as my teacher, Andre Dubus III at Emerson, said, “You’ve got to put your guts into it.” When we do that, we all feel it and we’re changed by it. That’s when, as an editor, I know I will remember that story.

NL: Sticking with your editing career, can you tell tell me a little about Brisbane Writers Workshop?

LED: Oh yeah. It’s funny how—I would like to have more agency in this [pointing to herself] female character, but I find that a lot of stuff I stumble into, and then try to swim.

When I first came here, I got a job for 18 months at an ad agency and hated it. I’m just not good with advertising when something in me’s looking for truth.

So I took on teaching at a local community college, and also, the University of Queensland had a weekend program, so I could work full time and also teach a class. I found I really enjoyed teaching, just as I watched some of these casual programs close.

It keeps me voracious, and it keeps me sharing, and it keeps me creating a community.

I had been teaching travel writing, memoir, fiction, novel, short story, and the schools got rid of them. So I thought, “Well, what if I run them myself and see what happens?”

At the same time, I was working at the publishing company. We had an intern program, so I would be training both mature-age students who were in their thirties and forties, as well as 19 year olds who’d join us for a semester in the publishing house. As I trained them in editing, I found that some of them would be so good at coaching authors on character or character flaws or narrative voice, or point of view, so I’d ask them to teach with me. I’d ask them to come into one of my workshops and run a lesson for an hour.

Writers need to be speakers, so these teaching experiences were wildly helpful for them. It was training for when their own books got published and they’d need to do an author talk or a reading.

I found that if I invited some of these folks to come and do a segment, they were terrified at first, but then they’d nail it. Some went on and pitched that very same concept to the local Writers Center as well, or ran a segment at a writer’s retreat.

I think I’m a Pied Piper, because I’m often gathering people.

Last year, I started an author gala through Brisbane Writers Workshop where we host readings while authors sell their own books and keep all the profits. There’s a raffle as well, where all the proceeds go to the Flinthart Residency, in honor of a dear author friend. We’re doing an open mic spooky thing on the 20th of October, with goofy Halloween stuff going on, it’s going to be great.

Brisbane Writers Workshop is all about learning, but also about getting writers out of their social anxiety and connecting and supporting one another. So I teach workshops to stay sharp and keep learning. I take workshops online, go to panels, come out for NecronomiCon and StokerCon, gather info and share it when I come back here.

It keeps me voracious, and it keeps me sharing, and it keeps me creating a community.

NL: I’m going to ask one-point-five more questions, and then I have a lightning round of some quick hits.

I think the larger, overarching question is: what’s the next big challenge for you? What’s the next big thing you’re working on? And then the point-five of that question is, what can you tell us about Where the Silent Ones Watch?

LED: Oh my gosh. I’ll take the point-five because I’m so proud of Where the Silent Ones Watch—and when I was at NecronomiCon in Providence, I scored an ARC—

[L.E. proudly displays her Advanced Readers Copy, with a beautiful cover design.]

—from Derek Hussey, the publisher of Hippocampus Press. It’s coming out October 6th, and I cannot get over the table of contents. Here we have Linda Addison, Steve Rasnic Tem. We have Lisa Morton, Tim Waggoner, Stephanie Wytovich, Lee Murray, Nancy Holder, Teel James Glenn. I could go on.

Wendy Wagner. I’ll stop. I’ll stop…

L. Marie Wood. Kyla Lee Ward. Aaron Dries. Oh my God. I’m so excited to be in this anthology. Edited by James Chambers, who’s a dream editor and whose mission is to shed light on William Hope Hodgson, what a talented, groundbreaking weird fiction writer he was.

My story, “Hangman’s Coming,” is inspired by The Boats of the “Glen Carrig,” which was William Hope Hodgson’s [novel]. I wanted to write about, again, a portion of my ancestors who came to America from southern Italy. They entered the country through New Orleans, which was terrifying at the time.

What I didn’t know and wasn’t taught in school was that America’s largest, en masse lynching happened in New Orleans around the time my family entered the country. In 1891, a mob of 10,000 had descended upon the New Orleans jailhouse after 11 men were acquitted for the murder of Police Chief David Hennessy.

After the trial was over, a mob of 10,000 raided the jail and dragged the men out and hanged them in the streets.

I wanted to try to understand this and to show why the people in my family came into the country and dispersed. Some went to Chicago, some to New York. They knew they were not wanted in the South. They were afraid they were going to be poisoned on the ship from the food. They were told not to eat the food on the on the ship as they crossed the Atlantic and to bring their own for the voyage.

So I took real life and placed it into weird fiction to make it palatable.

As far as what big thing is next, I have a couple of submission calls that I’m wrestling with and trying to finish. One’s set in the West Village in New York City, and I’ve been looking at family history there.

I’m also getting a little bit more involved in the Horror Writers Association Mental Health Initiative Committee, so I’ve been talking to Dave Jeffery and Lee Murray, because I see such wonderful things happening there. They have a Notable Works section, where horror writers will talk about a piece written by someone else that affected them, and gave them some sort of support or named something that they’re experiencing as well, whether it’s the grief of losing a parent or addiction or—I mean, it’s open, and it’s really impressive how that’s working out.

I also had a poem about my stutter accepted for an anthology. It’s a horror poem about how having a stutter is like living in a house haunted by the sea—affected by the elements and supernatural both inside and outside the walls. Writing about it scares me a little, because when I give the stutter attention, it can come back a little bit.

NL: Actually, one more question before the lightning round. Do you have a good entree into horror poetry, whether it’s an anthology or a specific author, that folks should look for? If this is a genre they’d like to explore?

LED: Yes. Heavy trigger warning, but I have Under Her Eye here, edited by Lindy Ryan and Lee Murray—this is about domestic violence. I wrote about the tarantella, which is the tarantula song. Which is a traditional wedding song now, but was also, when a young woman might say she was bitten by a tarantula—or maybe the village said she was bitten by a tarantula—and she would dance until she fainted or died.

This is an old, old bit of folk horror, and I just wondered what would make a young woman do that.

I would recommend checking out the Horror Writers Association’s Poetry Showcase. We’re at number XI, so there’s 10 already out there, and they’re phenomenal.

With a poem, as you know, it’s this feeling, and this theme, that just kind of condenses and explodes. And that’s what you’ll get with horror poetry. And it’s on the rise.

NL: Lightning round. Let’s just jump into it. Favorite cocktail, mocktail, or other beverage.

LED: Oh. Oh, gosh.

I love a mojito.

NL: Alien or Aliens?

LED: Alien.

NL: Yes. Not enough people say that one. And it is, in my opinion, the objective right choice—but why Alien for you?

LED: Because Ripley. Because final girl. Because she knew what was going on the whole time, and she survived.

And how good is that final scene? You think she’s gotten away, and little Jones and his sleeper, and the thing comes out of the ventilation, or whatever that bunch of hoses was.

NL: An excuse to hide the alien is what they were. [Both laugh.]

Okay, three more. If someone told you that you had to memorize an entire novel word for word, what book would you choose?

LED: Oh, God.

Oh, my God. It’s so hard. I have so many.

I have to look at my shelves. What do I pick?

NL: This is my spin on a desert island question. Like, if you had to spend all that time to carry something around in your head forever, what would it be?

LED: You know, I might really…

I love the classics, and I might go with The Odyssey of Homer just to be a jerk, because I love it.

I would love to see a woman’s version of that, but people might get mad about that.

NL: Do you mean like gender swapping Odysseus?

LED: Yeah yeah yeah.

I would love to see just that feminine energy on the journey. I love the journey motif, the journey story. And I would love to see a woman at sea, you know, and with comrades. And just how would that play out?

I mean, you can make it contemporary, you can make it classical, I don’t care. But I’d love to see what would unfold.

I mean, I love Madeline Miller’s Circe. It just illuminates what Circe’s character may have been like, you know? I ate that right up. You know how obnoxious these sailors would be, washing up on her island, eating her food, getting drunk, and then harassing her!

NL: And you know, The Odyssey would have been memorized originally, so that’s just a solid traditional choice.

Most underrated or sadly forgotten TV show.

LED: Okay, you know what? I’ll say this because it’s really fresh. I love The Last Kingdom series on Netflix.

NL: I’ve not even heard of it!

LED: I love the dialogue, I love the characters, I love the surprises. I love that I can’t stand certain characters. Aethelflaed, the queen to Alfred’s king. Alfred’s wife is awful. She’s just horrible.

And then she shows up with rockets in the last season there. I just love her. So I would say The Last Kingdom on Netflix, please don’t miss it.

There are also a lot of beautiful boys.

NL: I’m okay with that.

Okay, last question. Tell us about one thing we haven’t talked about yet today that lives rent free in your brain.

LED: There’s a song by Sneaky Sound System called “UFO,” and I will sometimes get that earworm playing on a loop. It’s really funny, and an Australian band.

NL: Thank you so much. I’m glad we could end with something funny.

LED: I was so pleased to see your email, because Necronomicon was like—it’s a world, and you meet so many people, but when people reach out after I’m so delighted, because we come for that. We need this community.

We have such strange, solitary lives as writers and teachers. You have all this work out there, but you need to feed your soul.

NL: And you’re always deep in other people’s work.

LED: Yes, yeah.

Our conversation continued for some time after this, but it drifted off into other directions that you, dear reader, will never know.